By Joe Healey HIST 566 Dr. Brandon Morgan Summer 2019

|

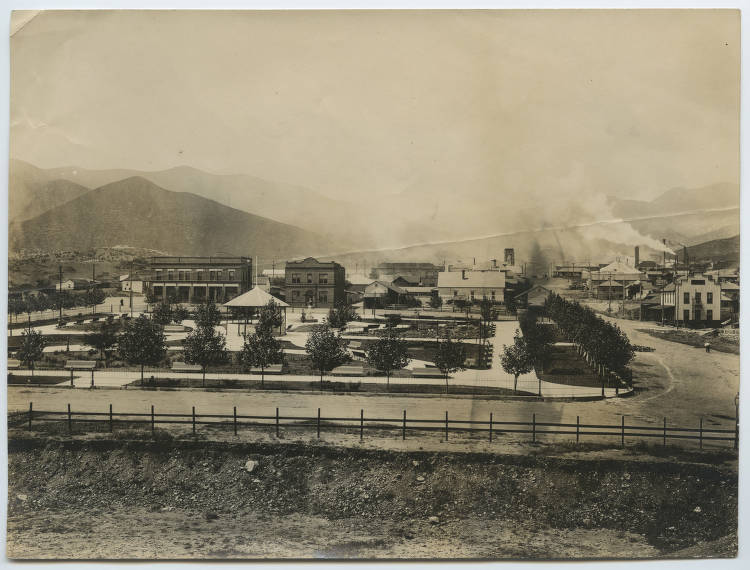

Cananea circa 1906 Wikimedia

|

Background to the Strike: Unrest at a Workaday Town

The Mexican Revolution was not a singular event organized in a quick fashion. The social, economic, and political unrest resulting from Porfirio Díaz's regime had been going on for decades. Díaz's policies favored elite land owners; they continued to claim public lands for themselves and court foreign investment. Foreign ownership of railroads, industry, and mining had grown exponentially during the Porfiriato. By 1911 a conservative estimation by Marion Letcher, chief U.S. consul to Mexico, declared that 78% of the mines and 72% of the smelters in Mexico were American-owned (qtd. in Wasserman 145).In the early 1900s, working class Mexicans were beginning to coordinate efforts in order to improve how they were treated and to complain about poor working conditions and pay. There had been long-term inequities regarding the treatment of Mexican workers. Unions were illegal, but workers led by Esteban Baca Calderón, Manuel Diéguez, and Juan Jose Ríos, created the Unión Liberal Humanidad, a workers’ “group” at the U.S.-owned Cananea Consolidated Copper Company mines. Questions arose whether this group was receiving outside influence from anarchist group Partido Liberal Mexicano (PLM) and the socialist unionizing force called the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

On June 1, 1906, Mexican workers at the Cananea mines, fed up with unfair treatment and bad working conditions went on strike. Of utmost concern, Mexican workers were being paid less than Americans at the mines and smelter. Calderón drafted the workers’ manifesto asking for, among other things, 5 pesos for an 8-hour workday and fair treatment for Mexican laborers. From the first moments, the strike took a dubious turn when mine owner, “Colonel” William C. Greene, rejected the workers’ demands. Two American foremen were killed which led to a bloody conflict some later dubbed the Cananea Mine Massacre. Approximately 26 Mexican workers were killed.

No single event sparked the Mexican Revolution in 1910, but some claim the Cananea strike was a precursor because it foreshadowed, in word and action, concepts that became central to the Revolution. Others say it was a local event that was yet another step toward uniting miners to other members of the lower classes.

How the strike was handled also had international ramifications, as the Cananea mine involved an American-owned business not forty miles from the U.S.-Mexico border.

Copper Mining in Cananea: Something's Not Right for Mexican Workers

|

| Cananea Mine Area from ? |

|

Cananea, Sonora Revolvy

|

Copper was highly sought after by countries around the world as they contined to industrialize. Copper was required for the ever-expanding electric grid being developed. Copper amounted to over 10% of Mexico's export-driven economy, only second to silver (Bulmer-Thomas 64). One of the more prominent copper mines was located in Cananea, Sonora. The town of Cananea was essentially a mine town with most of the domeciles and businesses being company-owned. Cananea Consolidated Copper Company was owned by an American named "Colonel" William C. Greene. His mining company, which often changed names as it changed its investment partnerships, was partly owned by the giant Rockerfeller mining company, Anaconda. U.S. mining companies in Mexico brought with them new technologies to extract copper. A workforce that could operate the modernized mining and smeltering processes was required. Many of these "qualified" men who became supervisors, overseers, and foremen came from the United States. In "Foreign and Native-Born Workers in Porfirian Mexico," historian Jonathan Brown states that,

"The foreigners-both workers as well as supervisors and owners-abrasively introduced their ways of working, which often violated the time-honored cultural norms observed by Mexican worker" (790).

Greene, an entrepeneur who also owned cattle ranches and other businesses in Northern Mexico, was viewed by the local workers as a harsh man. The image of the harsh American overseer was not uncommon. Sarah E.M. Grossman points out that the existence of cruel

American mine owners and mining engineers was often perpetuated because they had difficulites negotiating "their bureaucratic status most notably by embracing the westering frontiersman as a

self-image. This quintessentially American identity both reified their racial

status as white men" (116).

|

| W. Greene Find a Grave |

Racism and inequality manifested itself in a dual wage system. Mexicans were seen as inferior (in skill and intellect) and therefore were paid less than American miners. Workers complained about being paid in what amounted to "devalu[ed] Mexican scripts and currency [while] Americans recieved their pay inside Mexico in stable, ever more powerful U.S. currency and enjoyed higher wages to begin with" (Hart 64). According to the pro-worker Regeneracion at the time American workers received a pay rate of $5.00 (gold) versus $3.00 (silver) for Mexican workers (Magon 1). The early part of the century was marked with economic instability in Mexico, the price of silver had declined. Miners at the remote Cananea copper mine felt the economic downturn as their real wages declined as prices at company stores skyrocketed.

At the same time, William Greene was not faring well as a mine owner. In Pesos and Politics: Business, Elites, Foreigners, and Government in Mexico 1854-1940, John Wasserman explains that Greene was struggling in 1905-1906 with litigation and making a profit at the mine. Wasserman contends that Greene was not so much the villain as he was a victim of the times; he contends that miners in northern Mexico were typically paid more than other miners in Mexico because it was so close to the Mexican border where workers could cross the border to the U.S. in order to earn an even higher wage. They were also paid more than they would be if the worked in other careers in Sonora. With little support, Wasserman goes as far to say that the miners were treated well despite receiving less pay than their American counterparts (231).

One can argue that many of the problematic facets of the mining industry in the early twentieth century came to bear at Cananea. For Mexican miners, being the victims of racial descrimination and an unfair pay rate, working in unsafe conditions, and having no ability to advance beyond menial positions were at the forefront of their concerns. The financial pressures of operating a remote mine during an economic downturn and a racially insensitive attitude toward Mexican employees accounted for Greene's being blindsided by the activities on June 1st.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Strike in Sonora

In light of the harsh working conditions at mines in Mexico, one need only look at the headlines of The Mexican Herald on June 1, 1906: "Sixteen miners meet with certain death" (2). Twelve miners suffocated in a mine collapse in Temascaltepec while two others died in a mine accident in El Oro, Mexico. Life as a miner was dangerous. Strikes were occurring across the United States, most notably in Cripple Creek, Colorado.Though not directly tied to the events in Colorado or to the disasters in the state of Mexico, on June 1st, 1906 the miners at Cananea had enough with their ongoing situation. At mid-day, roughly 2,000 Mexican workers went on strike. Trouble began almost immediately as striking workers attempted to stop other miners who attempted to go to work; the mine overseers did not take kindly to that. Two American foremen scuffled with strikers. Shots were fired and the unarmed Mexican miners struck back with rocks and bricks. The first engagment resulted in two American men killed and a few Mexican miners injured. Who drew first blood would be called into question. For the next six days, the miners and security forces of the mines fought.

In the midst of the strike, the workers met with William Greene to present the WORKERS' DEMANDS aimed to rectify racial and labor inequities among other issues: Mexicans are as intellectually fit as foreign workers, removal of dual wage pay system, and change unsafe work conditions.

|

| Greene Trying to Calm the Storm Flickr |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Response to the Strike

Extra! Extra! Read All About It!

In the ensuing days, Mexican newspapers would define the strike in different ways. Their conclusions were drawn as news, often unverified, broke via telegraph and telephone.

When news reached Mexico City, the June 2 headlines regarding the situation read: "Strike, Race Riot, and Fire are Reported at Cananea" (The Mexican Herald 1). Although front page news (bottom billing), it relied on second hand information ("a report circulated here"), the editors of the paper were astute enough to know that a racial aspect permeated the strike. Yet, The Mexican Herald, an English language newspaper, written primarily for American businesmen in Mexico City, was quick to call it a "race riot" which infers an unruly and racially-motivated uprising by Mexicans against their white American employers. In no way, did the newspaper assume that Greene or his American employees may have been the instigators of the violence.

As the days went by more information unfolded. The first report by El Imparcial, the largest and one of the many pro-Diaz newspapers, ran on June 3: "Strikers Scandal in Cananea. Dead and Wounded." (1). El Imparcial accurately reported that the miners were upset with pay and discriminatory work practices.

For its part, The Mexican Herald on June 3, 1906 had a clearer picture of the events from correspondences between General Luis E. Torres who was on his way to Cananea and Ramon Corral Vice President of Mexico and its Minister of the Interior. The correspondence revealed that "[As] the strikers passed through the streets and in the center of town, a number of Americans in automobilies and on horseback fired right and left into the residences of Mexican families" (1). Around 15 Mexicans were killed and many wounded including one child on her way home from school. From the basis of the correspondences it determined "[S]o far from the lives of Americans being in danger at Cananea, the lives of Mexicans are those chiefly jeopardised" (1).

In the early moments, American consul in Cananea, W.J. Galbraith, held a different view. He was in a panic. Telegraph correspondences reported in The Mexican Herald show that on the day of the strike Galbraith sought American intervention from U.S. Secretary of State, Elihu Root: "Send assistance immediately to Cananea, Sonora, Mexico. American citizens are being murdered and property dynamited and we must have help" (1). Two days later he continued his plea: "Imperative that immediate assistance be rendered to American citizens at Cananea, Sonora, Mexico" (1).

In a telegram to home offices in New York on June 2, William Greene downplayed the whole event: "Authorities giving us every protection possible, assisted by employees of the company...The governor of Sonora, with troops, will arrive in the morning. We have the situation well in hand...The smelting and concentrating plants are uninjured. I expect the plants to be running at full capacity tomorrow" ("Mexican Government Rushes Troops" 2). It was in Greene's best interest to minimize the negative optics of a violent strike so it would not affect investment in his mine.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Outside Influence? Impact on a Pre-Revolutionary Nation.

Instead of claiming the event was led by everyday miners, Greene exclaimed in his correspondences with the home offices in New York,"The trouble was incited by a socialist organization that has been formed here by malcontents oppossed to the government"("Mexican Government Rushes Troops" 2).

Was this Greene trying to calm investors back in the U.S.? He knew the workers' demands were labor and pay-related. Was he merely being dismissive? Or perhaps Green was right. So what it the story?

Historians have taken basically two approaches when analyzing the direction of and influences in the strike at Cananea: a traditonal view that assserts outside political direction or influence and a revisionist view that looks at the events more locally as primarily a labor issue. According to Rodney D. Anderson, the former scholars generally feel that the labor conflicts during last five years of the Porfiriato were due to "anarch[ism], syndicalism or socialism and the agitation of their proponents" (96). They attribute the uprisings to socialist doctrines introduced to Mexico by a small group of intellectuals and in particular exiled members of Partido Liberal Mexicano (PLM) and eventually enlisting the workers in a struggle against the Diaz regime--and as some have argued--against the capitalist system itself" (96).

The Junto Organizadora del Partido Liberal Mexicano was a more radical offshoot of an main Liberal Party organization that was unhappy with the Diaz regime. The brainchild of the Magón brothers, Ricardo, Eduardo and Jose, and other exiled Mexican intellectuals, the PLM came out with its manifesto one month to the day after the Cananea strike. Its basic tenets denounced the Porfiriato and called for, among other things, the Mexican government to abide by Consititutional laws. It spoke directly to the concerns of the working class--one could almost say taken right from the Cananea miners' demands: "The establishment of 8-hour work day for all [Mexican] workers...[the removal of] varying pay scales for the same labor...[and] a minimum wage of $1 but more depending on the cost of living in certain regions" (7).

Although rumors had existed that the PLM had sent members to places such as Cananea to "exterminate Americans employed in and around mines" no evidence shows that ever occurred. Anti-Yankee sentiment and anarchistic ideas were a central part of Magon's PLM, but these ideas were stated less harshly in the striking miners' demands.

In his own letters to a friend shortly after the strike, Ricardo Magón expressed suprise by the strike in Cananea. He supported the workers' cause. Matters of a grander scale such as addressing the issues of a corrupt government were his ultimate goal: "The government is so infamous that it assassinates unarmed men, but it fears armed men...You have to root out evil. I hope my comrades of Cananea do not foget the outrage they have received...and agree that we work in a single day and at the same time in many parts of the republic." He shows no knowledge or inside information of the strike in his letters. Magón mostly hopes the strike inspires the workers to lash out at the government. In a June 15, 1906 article "Los Disturbios de Cananea: Porfirio Diaz es el Responsible" in his Regeneración, Magón declared that "We didn't excite the workers at Cananea for revolutionary purposes or any others who made the uprising" (1). While historians cannot just take Magón at his word, it's unlikely he played an organizing role in the strike.

To deny, as revisionist theories do, there was any contact between or influence of the PLM and Mexican miners during the early 1900s would be erroneous. In fact, in November 1905 Esteban Calderon, fed up with the inequities at the mine, wrote to a friend (and connection of Magon) inquiring about the PLM. He stated that he could "no longer hold his silence" on inequities at Cananea or the issues resulting from the Porfiriato. Calderon declared, "Here, there are already many citizens affiliated with the cause for freedom; I am one of them. I sympathize with the progressive idea movement. I consider the Porfiriato that weighs on the people and the only way to combat it is by the union of liberal or independent men" (29-30). He goes on to say that the people of Cananea are growing impatient and would like to replace the government that is made up of "impudent lackeys" and replace it with one based on intelligence, justice, and freedom (30). These are hardly words of an apolitical striking miner. The unfair treatment at the mines had pushed him beyond merely worker demands. Soon after, he received word directly from Ricardo Magón. The relationship had formed.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) union movement and another union force called the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), were organizations PLM leaders worked closely with, and also influenced Calderon. According to historian James Cockcroft, Magón and his PLM compatriots helped recruit thousands of members for the IWW in Mexico (qtd. in Anderson 102).

The IWW had only existed for a year at the time of the Cananea strike, so its membership was quite small in Mexico, but the WFM was active in the southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico. By 1905, the WFM alone had an estimated 1500 members at Cananea (Gonzales "United States Copper Companies" 667). Three Mexican miners who had some IWW and WFM affiliations were Esteban Baca Calderón, Manuel Diéguez, and Juan Ríos who created the Unión Liberal Humanidad (ULH) and Club Liberal de Cananea (CLC) at Cananea in September 1905. The first article of its Constitution pledged alliegence to the Magón branch of the PLM (37). Unions were banned in Mexico at the time so all of this was quite dangerous.

By the time of the strike Calderón wrote the workers' demands, the first third of which are work-related. The second two-thirds of the workers' memo, which was added to a pamphlet distributed to the miners, speaks to a broader audience of Mexico's workers and its populace about the failings of the Mexican government:

The verbiage and ideology is similar to the PLM and its manifesto. It also sounds like the grander vision held by the PLM. To say there were directives being sent by exiled PLM leaders would be going too far. Alan Knight points out that "workers' demands were frequently couched in terms of constitutional rights and the legacy of Juarismo" (55).

It should be known, Calderón and the others were definitely inspired by the PLM, IWW, and WFM. Shades of the IWW's motto "an injury to one is an injury to all" was also evident. The PLM and the Cananea workers' demands went beyond everyday miner's rights to address the governance of Mexico as a whole, its treatment of its citizens, and the tyranny of its leaders. The strike could be seen as a proving ground for the Revolution which would come four years later.

But in June 1906, the men were striking miners faced with other challenges. At the end of the strike and uprising none of the workers' demands were met. Peace was restored by the local authorities and federal army.

The Cananea Strike of 1906 had the markings of PLM language and vision which is echoed in the anarchistic PLM manifesto--distributed one month after the strike. Magón was not the architect of the strike, though he was an advocate. That is evident in his correspondences. Historians such as Jonathan Brown would argue that the PLM was less involved because the strikers' demands did not attempt to permanently disable the system, but "only expressed a desire for security and dignity within the system" ("Foreign Workers" 798) and struck to gain equality with foreign workers, but that seems to be refuted by Calderón's own letters and proclamations. Ultimately, the workers were upset--though probably not surprised--that Governor Rafael Izabal, President Diaz, and the federal authorities did not stand with them against their oppressive foreign employer. Rodney D. Anderson, also takes the revisionist view, feels that the workers took their political inspiration from what they saw as Mexican ideals. He states that broader goals of the working class were becoming more evident in "workers' letters, flyers, petitions and newspapers [which] expressed most often such goals as fair treatment from the industrialists, aid and comfort from their government, and social, economic and political equality with other classes in society" (97). Whatever their inspiriation, these were the early whispers of the common Mexican soon to be echoed in the Revolution.

The Junto Organizadora del Partido Liberal Mexicano was a more radical offshoot of an main Liberal Party organization that was unhappy with the Diaz regime. The brainchild of the Magón brothers, Ricardo, Eduardo and Jose, and other exiled Mexican intellectuals, the PLM came out with its manifesto one month to the day after the Cananea strike. Its basic tenets denounced the Porfiriato and called for, among other things, the Mexican government to abide by Consititutional laws. It spoke directly to the concerns of the working class--one could almost say taken right from the Cananea miners' demands: "The establishment of 8-hour work day for all [Mexican] workers...[the removal of] varying pay scales for the same labor...[and] a minimum wage of $1 but more depending on the cost of living in certain regions" (7).

Although rumors had existed that the PLM had sent members to places such as Cananea to "exterminate Americans employed in and around mines" no evidence shows that ever occurred. Anti-Yankee sentiment and anarchistic ideas were a central part of Magon's PLM, but these ideas were stated less harshly in the striking miners' demands.

In his own letters to a friend shortly after the strike, Ricardo Magón expressed suprise by the strike in Cananea. He supported the workers' cause. Matters of a grander scale such as addressing the issues of a corrupt government were his ultimate goal: "The government is so infamous that it assassinates unarmed men, but it fears armed men...You have to root out evil. I hope my comrades of Cananea do not foget the outrage they have received...and agree that we work in a single day and at the same time in many parts of the republic." He shows no knowledge or inside information of the strike in his letters. Magón mostly hopes the strike inspires the workers to lash out at the government. In a June 15, 1906 article "Los Disturbios de Cananea: Porfirio Diaz es el Responsible" in his Regeneración, Magón declared that "We didn't excite the workers at Cananea for revolutionary purposes or any others who made the uprising" (1). While historians cannot just take Magón at his word, it's unlikely he played an organizing role in the strike.

To deny, as revisionist theories do, there was any contact between or influence of the PLM and Mexican miners during the early 1900s would be erroneous. In fact, in November 1905 Esteban Calderon, fed up with the inequities at the mine, wrote to a friend (and connection of Magon) inquiring about the PLM. He stated that he could "no longer hold his silence" on inequities at Cananea or the issues resulting from the Porfiriato. Calderon declared, "Here, there are already many citizens affiliated with the cause for freedom; I am one of them. I sympathize with the progressive idea movement. I consider the Porfiriato that weighs on the people and the only way to combat it is by the union of liberal or independent men" (29-30). He goes on to say that the people of Cananea are growing impatient and would like to replace the government that is made up of "impudent lackeys" and replace it with one based on intelligence, justice, and freedom (30). These are hardly words of an apolitical striking miner. The unfair treatment at the mines had pushed him beyond merely worker demands. Soon after, he received word directly from Ricardo Magón. The relationship had formed.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) union movement and another union force called the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), were organizations PLM leaders worked closely with, and also influenced Calderon. According to historian James Cockcroft, Magón and his PLM compatriots helped recruit thousands of members for the IWW in Mexico (qtd. in Anderson 102).

By the time of the strike Calderón wrote the workers' demands, the first third of which are work-related. The second two-thirds of the workers' memo, which was added to a pamphlet distributed to the miners, speaks to a broader audience of Mexico's workers and its populace about the failings of the Mexican government:

|

| Esteban Baca Calderón Repositorio del Patrimonio Cultural de Mexico |

"A government that is made up of ambitious men who tire the patience of the people with their criminally self-interested activities, elected by the worst of them in order to help them get rich: Mexico does not need this. People, rise up and go forward. Learn what it is that you have forgotten. Gather together to discuss your rights. Demand the respect that is owed you. Each Mexican who is mistreated by foreigners is worth the same or more than them, if he unites with his brothers and demands his rights."

The verbiage and ideology is similar to the PLM and its manifesto. It also sounds like the grander vision held by the PLM. To say there were directives being sent by exiled PLM leaders would be going too far. Alan Knight points out that "workers' demands were frequently couched in terms of constitutional rights and the legacy of Juarismo" (55).

It should be known, Calderón and the others were definitely inspired by the PLM, IWW, and WFM. Shades of the IWW's motto "an injury to one is an injury to all" was also evident. The PLM and the Cananea workers' demands went beyond everyday miner's rights to address the governance of Mexico as a whole, its treatment of its citizens, and the tyranny of its leaders. The strike could be seen as a proving ground for the Revolution which would come four years later.

Foreshock of the Revolution

Calderón, Dieguez, and Rios were soon arrested and imprisoned after the strike was put down. While in jail, they solidified their ideology. Not until the Revolution was underway and Diaz was deposed did they freed from jail. In 1911 President Madero freed them. They returned to the mines briefly to help the ULH. Eventually, they made their mark as Constitutionalists fighting under General Obregón, who would later become president. Calderón became acting governor of Colima. Dieguez later became governor of his home state of Jalisco. Rios became Secretary of War during Obregón's presidency. The leading men of Cananea became leading men of the Revolution (against Huerta) and authorities at the regional and national level.| Juan Jose Rios Universidad de Colima |

But in June 1906, the men were striking miners faced with other challenges. At the end of the strike and uprising none of the workers' demands were met. Peace was restored by the local authorities and federal army.

|

| Manuel M. Dieguez Repositorio del Patrimonio Cultural de Mexico |

The Cananea Strike of 1906 had the markings of PLM language and vision which is echoed in the anarchistic PLM manifesto--distributed one month after the strike. Magón was not the architect of the strike, though he was an advocate. That is evident in his correspondences. Historians such as Jonathan Brown would argue that the PLM was less involved because the strikers' demands did not attempt to permanently disable the system, but "only expressed a desire for security and dignity within the system" ("Foreign Workers" 798) and struck to gain equality with foreign workers, but that seems to be refuted by Calderón's own letters and proclamations. Ultimately, the workers were upset--though probably not surprised--that Governor Rafael Izabal, President Diaz, and the federal authorities did not stand with them against their oppressive foreign employer. Rodney D. Anderson, also takes the revisionist view, feels that the workers took their political inspiration from what they saw as Mexican ideals. He states that broader goals of the working class were becoming more evident in "workers' letters, flyers, petitions and newspapers [which] expressed most often such goals as fair treatment from the industrialists, aid and comfort from their government, and social, economic and political equality with other classes in society" (97). Whatever their inspiriation, these were the early whispers of the common Mexican soon to be echoed in the Revolution.

By the time the strike was over what mattered more to Mexicans than a failed strike at a farflung mine was the realization that local and federal authorities had sided with a foreign company over the Mexican workers. The words of the workers' were writ loudly: Mexicans should be worth as much, if not more, than the foreigner.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Did U.S. Break International Law? Was Porfirismo Favoring Foreigners?

The six-day strike was resolved, but the aftermath raised many questions. W.J. Galbraith's panicked requests for U.S. military intervention in Cananea opened the door not only to national issues but international ones as well.

From the late 19th century to the early 1900s, American companies operating in Mexico felt support from Diaz's federal government, but often had issues with local goverment officials. Historian Jonathan Brown states, "But for all the benefits foreigners were bringing to the country, the outsiders believed they deserved better. That is why they rebuked public authority in Mexico" (13). This played-out in Cananea during the strike. Local officials in Sonoroa were slow to act. Governor Izabal and many federal troops led by General Luis Torres were in the midst of a war with the Yaqui Indians hours away in southern Sonoroa. Cananea mining security forces were overwhelmed by the strike and ensuing violence.

| Rynning's Arizona Rangers in 1903 from GunWatch Blog |

American War Office telegrams show that the wheels were in motion for American calvary to come to the aid of Greene and the American miners at Cananea. On June 2 Army correspondence captured in The Mexican Herald stated that "Major Watts, with his squadron, leaves for Naco [Arizona] tomorrow night, hurry orders. Will render all assistance possible, observing law" (2). This last statement shows that the U.S. was well aware of abiding by international law.

U.S. Secretary of State Elihu Root mentioned to U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, "[We] would be glad of any suggestion from the Government of Mexico as to the course which we may take to provent violation of international obligations on the part of our citizens, to help prompt peace and safety" ("Mexican Government Rushes Troops" 1). The U.S was seemingly racing to provide help, but at the same time, cognizant of the ramifications. Mexico was adamant about the sovereignty of its borders, rightfully still a sensitive issue owing to the Mexican-American War and the ensuing Gadsden Treaty of 1854.

Just a day after the strike had begun the editors of The Mexican Herald cited an Arizona news dispatch that stated: "Arizona Rangers with a large posse have left Bisbee [Arizona] for Cananea" (1) An interesting editorial note follows the news report: "It is hardly necessary to say that the Arizona Rangers cannot penetrate into or exercise acts of authority in Mexico territory" (1).

William Greene's June 2 personal telegraphed message exclaimed the uprising was under control and mentioned one peculiar item: "Bisbee, Douglas and Naco have sent 200 volunteers to aid in preserving order" ("Mexican Government Rushes Troops" 2).

|

| Thomas Rynning AZ Memory Project |

Captain Thomas Rynning (former Rough Rider with Teddy Roosevelt) and his Arizona Rangers who had illegally crossed the border on other instances, looked to be moving in that direction once again. According to D.L. Turner, Rynning, who had a working relationship with William Greene, had previously come across the border with his Arizona Rangers to catch cattle rustlers on Greene's ranch in Sonoroa (262). Rynning and his Arizona Rangers were known for busting mine strikes in Arizona and the southwestern U.S. and were widely known for their "propensity to bend the law" (Turner 260).

At the early stages of the strike Governor Rafael Izabal, the capitan of the Sonoran rurales, Colonel Emilio Kosterlitsky, and regional federal General Luis Torres were not near Cananea. Green phoned Rynning to come to his aid as it would be a while before the rurales or federal troops would arrive.

Rynning just so happened to be near Bisbee, Arizona where the governor and general were soon to arrive. A skirmish ensued there as a mob of Americans trying to rush across the border were met by Mexican border guards. Rynning calmed things down and selected 300 men--some of whom were Arizona Rangers in what Rynning called a "bronco army" (296) to cross the border. In his 1931 autobiography, Rynning recounts that he ordered all telegrams from Arizona Territory governor, Joseph Kibbey, be held until his return. Rynning knew the governor would be ordering him to stand down (297).

Some sources say that Izabal allowed the Arizona Rangers to cross the border as long as they were not in uniform, swore allegiance to Mexico, and would follow his orders (Turner 272). A June 6 news report stated that "American forces did not enter Mexico" ("Cananea Reports" 1). William Greene's letter in June 6's The Mexican Herald in stated, "Private individuals from Arizona who have friends and relatives at Cananea joined the efforts" ("Cananea Reports" 1). From Rynning's recollection, Arizona Rangers were but a few of the armed men--mostly miners and townsfolk from Bisbee--who were part of the group. Who they really were and who allowed them to cross was unclear at the time.

|

| Governor Izabal Cronicas de Cananea |

Exasperated, Izabal and Torres agreed. Rynning stated that it wasn't the first time he was commissioned as a volunteer of the Mexican Army; he had done so before but "kept that information to myself" (199).

Rynning knew Colonel Emilio Kosterlitsky who was in charge of the Mexican rurales. Their experience fighting and chasing Indians across the borderlands brought them together on more than one occassion. They were two renegade lawmen on different sides of the border.

According to Michael J. Gonzales,

|

| Kosterlitsky TrueWest |

In his autobiography, Rynning clearly explains that he and his men (led mostly by Arizona Rangers) though remaining under the orders of Izabal and Torres "disperse[d] a bunch of Mexicans who were shooting from behind a lot of bowlders [sic] on a point that comes out from the mountains south of Ronquillo, and we chased them out of there and disarmed them" (301). Upon the arrival of Kosterlitsky and the rurales, Rynning's men gathered American families and travelled back to the U.S. on train.

It would be a political nightmare if Izabal had allowed American troops to cross the border and fight. Every day underground wheeling-and-dealing aside, this moment was being captured for the whole nation to see and read about. National sovereignty was sacrasant. It seemed that was the case, but on June 7, 1906 El Imparcial came to Izabal's defense, pointing out that the Americans who came from Bisbee were merely "negotiators who did not partake in the events neither for or against the strikers. They and Mr. Greene left almost as soon as they arrived" (1). The report in El Imparcial also attempted to clear Governor Izabal: "The forces he summoned were from Naco, Mexico not Naco, Arizona" (1).

This news report contradicts Governor Izabal's later profession that he demanded before they departed the train in Cananea that any armed Americans return to the border via the same train upon which they arrived. D.L. Turner suggests that Greene purposefully had the train "break down" and thus the American "volunteers" could not return immediately (279).

The impact of how Izabal and Diaz could allow the U.S. to come across without repudiation became proof for future Revolutionaries that the Porfiriato was selling-out to foreign powers. It reinforced, in a public way, that local officials and federal authorities sided with foreigners, not Mexicans. Ricardo Magon spoke fervently against Izabal and Diaz in a June 15 Regeneracion article, "Izabal has inflicted a hurt, a hurt called: TREASON...The treacherous dictatorship continues its deplorable tradition" (1). Liberal Mexican intellectuals and working class miners had yet another sign that foreigners took precedent over Mexicans under the Porfiriato.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Cananea Strike of 1906: A Narrative of Mexico

General Torres broke the strike and workers had the choice to return to work or be drafted into the army. If this were the end of the story, it would barely have a mention in the annals of history. But, it wasn't the end. It was a glimpse into the future. There would be gains and losses. Demands and promises made and broken. Waiting and fighting.Little seemed to change in the immediate aftermath of the Cananea strike--for Greene, Izabal and the federal government life apparently went on as usual. But for the miners life had changed. Their demands were not met and many were expelled for joining a union or having PLM affiliations. The leaders were imprisoned. Those that returned to the Cananea mine found themselves under "increased social and military control" (Gonzales 652).

But soon, mounting pressure on Porfirio Diaz to curtail the autonomy and influence of foreign entities in Mexico would prove a difficult measure. Anti-foreign sentiment rose. The reverberations of Cananea would be felt as miners became even more politicized and radicalized. They looked for allies in their cause and found many. In the coming years they would be important in the fight against the Diaz regime, forged by even stronger union ties, and allied themselves with Revolutionary leaders. Ultimately, their cause would be heard by new leaders and a new Constitution that put Mexican's rights at the forefront and provided miners with the rights they once demanded at Cananea. Success did not come all at once and did not come without sacrifice, but that was nothing new to the Mexican miners at Cananea.

|

| Cananea Miners 1906 |

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Works Cited

Primary Sources:

Calderon, Esteban Baca. Juicio Sobre La Guerra del Yaqui y Genesis de

La Huelga de Cananea. 2nd ed. Mexico: Centro De Estudios

Historicos De Movimiento Obrero Mexicano, 1975.

"Cananea Reports Were Greatly Exaggerated." The Mexican Herald. HNDM. June 6, 1906. Accessed July 7, 2019. http://www.hndm.unam.mx/consulta/publicacion/visualizar/

558075be7d1e63c9fea1a34d?anio=1906&mes=06&dia=06&tipo=publicacion

"Cananea Workers' Demands (1906)." Accessed July 9, 2019.

558075be7d1e63c9fea1a34d?anio=1906&mes=06&dia=06&tipo=publicacion

"Cananea Workers' Demands (1906)." Accessed July 9, 2019.

https://cole2.uconline.edu/courses/178232/files/15572155/download?wrap=1

"Carta de Ricardo Flores Magón al Señor Don Gabriel A. Rubio. Estan Dispuestos los Compatriotas de Cananea a Hacerse Respetar?" 500 Años de México en Documentos. July 27, 1906. Accessed July 7, 2019. http://www.biblioteca.tv/artman2/publish/1906_199/Carta_de_Ricardo_Flores_Mag_n_al_Se_or_don_Gabriel_A_Rubio_Est_n_dispuestos_los_compatriotas_de_Cananea_a_hacerse_respetar.shtml.

"Carta de Ricardo Flores Magón al Señor Don Gabriel A. Rubio. Estan Dispuestos los Compatriotas de Cananea a Hacerse Respetar?" 500 Años de México en Documentos. July 27, 1906. Accessed July 7, 2019. http://www.biblioteca.tv/artman2/publish/1906_199/Carta_de_Ricardo_Flores_Mag_n_al_Se_or_don_Gabriel_A_Rubio_Est_n_dispuestos_los_compatriotas_de_Cananea_a_hacerse_respetar.shtml.

"Escandolos los Huelguistas en Cananea." El

Imparcial. HNDM. June 3, 1906. Accessed July 7, 2019. http://www.hndm.unam.mx/consulta/publicacion/visualizar/558a371b7d1ed64f16d330c9?anio=1906&mes=06&dia=03&tipo=pagina&palabras=imparcial.

Junta Organizadora del Partido Liberal Mexicano.

"Programa del Partido Liberal Mexicano." Plana. July 1, 1906.

Accessed July 10, 2019. http://www.ordenjuridico.gob.mx/Constitucion/CH6.pdf.

"Los Disturbios de Cananea." Regeneracion. HNDM. June 15, 1906. Accessed July 26, 2019.

http://www.hndm.unam.mx/consulta/publicacion/visualizar/558075be7d1e63c9fea1a3fe?anio=1906&mes=06&dia=15&tipo=publicacion

"Los Disturbios de Cananea." Regeneracion. HNDM. June 15, 1906. Accessed July 26, 2019.

http://www.hndm.unam.mx/consulta/publicacion/visualizar/558075be7d1e63c9fea1a3fe?anio=1906&mes=06&dia=15&tipo=publicacion

"Mexican Government Rushes Troops to the Scene of Trouble in Sonora." The Mexican Herald. HNDM. June 3, 1906. Accessed July 7, 2019. http://www.hndm.unam.mx/consulta/publicacion/visualizar/558075be7d1e63c9fea1a34d?intPagina=1&tipo=publicacion&anio=1906&mes=06&dia=03

Noticias de Discoursos Cananea." El Imparcial. HNDM. June 7, 1906. Accessed July 7, 2019. http://www.hndm.unam.mx/consulta/publicacion/visualizar/558075be7d1e63c9fea1a2fb?anio=1906&mes=06&dia=07&tipo=publicacion

Rynning, Thomas Harbo, Alfred A. Cohn, and Joe Chisholm. Gun Notches: The Life Story of a Cowboy-Soldier. Vol. 2. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1970.

Rynning, Thomas Harbo, Alfred A. Cohn, and Joe Chisholm. Gun Notches: The Life Story of a Cowboy-Soldier. Vol. 2. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1970.

“Strike, Race Riot and Fire are Reported at Cananea.” The

Mexican Herald. HNDM. June 2, 1906. Accessed July 7, 2019. http://www.hndm.unam.mx/consulta/publicacion/visualizar/558075be7d1e63c9fea1a34d?anio=1906&mes=06&dia=02&tipo=publicacion.

Secondary Sources:

Bulmer-Thomas, V. The

Economic History of Latin America since Independence. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Anderson, Rodney D. "Mexican Workers and the Politics of

Revolution, 1906-1911." The Hispanic American

Historical Review 54, no. 1 (February 1974):

94-113. Accessed July 8, 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2512841.

Brown, Jonathan C. "Foreign and Native-Born Workers in

Porfirian Mexico." The American Historical Review 98, no. 3 (June 1993): 786-818. Accessed July 8, 2019. doi:10.1086/ahr/98.3.786.

Gonzales, Michael J. "United States Copper Companies,

the State, and Labour Conflict in Mexico, 1900–1910." Journal of Latin American Studies 26, no. 3 (October 1994): 651-81. Accessed July 5, 2019.

doi:10.1017/s0022216x00008555.

Hart, John M. Revolutionary Mexico: The Coming and Process of the Mexican Revolution. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1997.

Grossman, Sarah E. M. Mining the Borderlands: Industry, Capital, and the

Emergence of Engineers in the Southwest Territories, 1855-1910. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2018.

Knight, Alan. "The Working Class and the Mexican

Revolution, c. 1900–1920." Journal of Latin American Studies 16, no. 1 (May 1984): 51-79. Accessed July 5, 2019.

doi:10.1017/s0022216x0000403x.

Turner, D. L. "Arizona’s 24-Hour War: The Arizona

Rangers and the Cananea Copper Strike of 1906." The Journal of

Arizona History 48, no. 3 (2007): 257-88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41697060.

Wassernman, Mark. The Mexican Revolution: A Brief History with Documents. New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2012.

Wasserman, Mark. Pesos and Politics: Business, Elites, Foreigners, and

Government in Mexico, 1854-1940.

Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ. Press, 2015.

Photographs and Images:

"Arizona Rangers 1903." Gunwatch. Accessed July 18, 2019.

http://gunwatch.blogspot.com/2014/10/arizona-rangers-1903.html

"Esteban Baca Calderon." Repositorio del Patrimonio Cultural de Mexico. Accessed July 9, 2019.

https://www.mexicana.cultura.gob.mx/es/repositorio/detalle?id=_suri:FOTOTECA:TransObject:5bc7d7147a8a0222ef101a9c&word=Esteban%20Baca%20Calderon&r=1&t=546

"Cananea circa 1906." Wikimedia. Accessed July 7, 2019.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/13/Cananea%2C_Sonora%2C_ca_1908.jpg

"Cananea Mine Area." Accessed July 28, 2019.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/40168090?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

"Cananea Miners 1906." Arizona Daily Star. June 3, 2013. Accessed July 29, 2019.

https://bloximages.chicago2.vip.townnews.com/tucson.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/3/12/312fb5fb-4a99-5f6e-bc03-33104f36867b/51abeee9aca5a.image.jpg

"Cananea, Sonora map." Revolvy. Accessed July 8, 2019.

https://www.revolvy.com/page/Cananea?stype=topics&cmd=list

"Cananea Strike." Comintern. Accessed July 7, 2019.

http://ciml.250x.com/archive/events/english/1906_mexico/1906_cananea_strike.html

"Manuel M. Dieguez." Repositorio del Patrimonio Cultural de Mexico. Accessed July 9, 2019.

https://www.mexicana.cultura.gob.mx/es/repositorio/detalle?id=_suri:FOTOTECA:TransObject:5bc7d7187a8a0222ef10255c&word=Manuel%20M.%20Dieguez&r=6&t=6968

"William C. Greene." Find a Grave. Accessed July 26, 2019

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/19768190/william-cornell-greene

"William C. Greene Trying to Calm the Storm." Flickr. Accessed July 8, 2019.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/smu_cul_digitalcollections/4701453220

"Rafael Izabal." Cronicas de Cananea. May 29, 2019 Accessed July 22, 2019

http://cronicasdecananea.blogspot.com/

"Kosterlitsky." True West Magazine. September 23, 2016. Accessed July 28, 2019

https://truewestmagazine.com/kosterlitzky-the-mailed-fist-of-mexico/

"Magon." Repositorio del Patrimonio Cultural de Mexico. Accessed July 9, 2019.

https://www.mexicana.cultura.gob.mx/es/repositorio/detalle?id=_suri:INEHRM:TransObject:5bcbda677a8a0222ef14823c&word=Ricardo%20Flores%20Magon&r=0&t=4307

"Juan Jose Rios." University of Colima. Accessed July 28, 2019.

http://ceupromed.ucol.mx/nucleum/BIOGRAFIAS/biografia.asp?id=54

"Thomas Rynning." Arizona Memory Project. Accessed July 25, 2018.

https://azmemory.azlibrary.gov/digital/collection/histphotos/id/5228/

No comments:

Post a Comment